By Susan Broomhall, The University of Western Australia

The makers of the next instalment of Sid Meier’s strategy game, Civilization VI, have just announced the debut of a new protagonist to lead France in the franchise: Catherine de Medici (1519–1589), consort of Henri II of France, later regent and mother to three kings, who dominated courtly life in France for much of the later sixteenth century.

Refreshingly, the associated First Look: France pre-release promotional presentation on the Civilization website contains none of the common ‘despite her sex’ descriptions of Catherine’s political work.

Connected to the appearance of Catherine is the sixth instalment’s ‘Unique Improvement’: the château. As the release explains, ‘Numerous chateaus remain to this day as tourist attractions, including Catherine’s favorite, the Chateau de Chenonceau, site of many of her spectacular nighttime parties and the first fireworks display seen in France’. This appears to recognise recent scholarship that has done much to demonstrate cultural investment of this kind by women and men as gendered political work. Catherine’s impressive architectural and horticultural complexes, ritual ceremonies, display of imported and luxury objects and natural history collections asserted her political identity, that of the Valois dynasty and their legacy. These were not accumulations of things by an extravagant spendthrift. Catherine’s collecting and patronage of foreign exotica, precious goods, exclusive sites and special events, and her investment in luxury innovation, constituted strategic economic and political interventions.

The game developers have identified Catherine’s leadership strength in the game as stemming from espionage. Ladies-in-waiting, acting as a spy network, create further player opportunities as sources for additional knowledge. This too reflects recent scholarship that has done much to shift perspectives concerning women’s communicative work from ‘gossip’ to strategic political intelligence gathering and networking in the courtly environment.

Interpretation of Catherine’s activities has too often amounted to repeating suggestive references from contemporaries and later historians regarding her material profligacy, ruthless willingness to engage in violence and the sexualised politics of her attendant ladies. One can equally locate contemporary voices of praise for Catherine, but these appear have had less impact in the public and historical imagination. Few of those who cite these negative assessments delve deeper into their contexts, as foreigners writing home to their paymasters, as disgruntled artists and courtiers who did not receive her patronage, or as those who simply reported the hearsay of printed propaganda that was produced as part of the wars of religion.

Why is such vitriol against female political leaders continually reproduced, across centuries, often with little or no rigorous analysis? For Catherine was by no means the only consort who has met such interpretive treatment by contemporaries or those producing the past. Margaret of Anjou, consort of Henry VI of England, was Shakespeare’s ‘She-wolf of France, but worse than wolves of France’ (Henry VI: Part III, Act 1, Scene 4). One might add several women on their respective national stages in recent years who have met not dissimilar treatment.

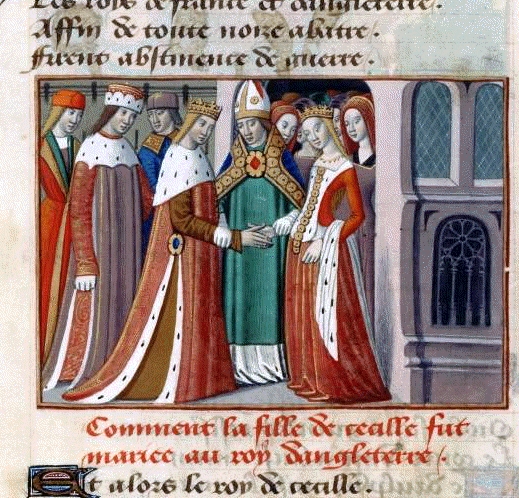

Ideas about women’s emotions underpinned anxieties about their power. For some, their potential love and loyalty to others beyond the realm was dangerous. Catherine was, after all, perceived, like her predecessor Margaret of Anjou or later Marie Antoinette, to be a woman from elsewhere. In fact, although Catherine was raised on the Italian peninsula, her mother was a French noblewoman. A culture of concern about power in the hands of a ‘foreign’ queen understood, however, that a consort’s devotion to her own natal dynasty rather than that of her husband compromised her trustworthiness.

Early modern guidebooks and prescriptive literature regularly insisted upon women’s emotional investment in their identities as mothers who nurtured, guided and instructed their children. Yet when consorts produced children who secured the future of their marital dynasties and sought to protect their interests through political labour, they were still a disruptive presence on the political scene. In frustration, the Spanish ambassador to the French court, Frances de Alavá y Beamonte, terms Catherine in his reports to Philip II of Spain a proud ‘lioness’ who would not allow her sons to meet him without her.

Emotions likewise structured Catherine’s political agency in practice. It was as a mother and a widow that she had access to power. Civilization VI depicts her in the black garb for which she was famous, through which her gendered grieving and capacity for political engagement were simultaneously produced.

Women in positions of power were not only unsettling to contemporaries, but continue to provoke strong feelings in those who have crafted narratives of the past. Describing Margaret of Anjou at her marriage to Henry VI in April 1445, medieval historian Paul Murray Kendall declares her ‘already a woman: passionate and proud and strong-willed’.[1] Margaret had just turned 15. Catherine’s most recent popular biographer, Nancy Goldstone, sees her as an ‘unscrupulous mother’ and a ‘relentlessly calculating power broker’.[2]

Historical writing is an emotional epistemological practice that shapes our encounter with powerful women of the past. And it is one in which women’s political agency and acts have often been effaced in favour of more dramatic and emotionally compelling narratives of their material and political greed. The former approach requires imaginative thinking — beyond official roles and conventional sources of government actions — to reveal complex political worlds in operation. The second both silences women’s own voices and presumes to speak for them.

Women in power continue to generate a wide range of emotional actions and reactions. In our own era, witness the international response to then Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s speech addressing misogyny, delivered 9 October 2012 in the Australian Federal Parliament. Rob Davidson composed the choral work, ‘”Not Now, Not Ever!” (Gillard Misogyny Speech)’, performed by The Australian Voices, stating that as ‘the music goes on, it passes into something more serious, and (it is hoped) we hear the Prime Minister as a woman experiencing very real emotions’.[3]

It behoves us to scrutinize carefully productions of women’s afterlives. How we understand the past and choose to portray it shapes our present and future.

Susan Broomhall was a Foundation Chief Investigator in the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. She worked in the Shaping the Modern Program at The University of Western Australia. Susan’s projects analysed medieval and early modern objects and emotions, particularly as they are presented in modern museum, heritage and tourism environments. Her research explored: i) the interpretation of medieval and early modern objects in the history of emotional processes and practices; ii) the affective origins of specific medieval and early modern objects; iii) the emotional interpretation of medieval and early modern objects in museum, gallery and tourism contexts; iv) affective materiality. In October 2014, she became an Honorary Chief Investigator, having taken up an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship within the Centre. Her new research project focuses on emotions and power in the correspondence of Catherine de Medici. This study of the leading female political protagonist of the era will provide new insights into early modern strategies of emotional expression, letter-writing and political power, and a new view of Catherine’s own activities.

[1] Paul Murray Kendall, Richard the Third (New York: W.W. Norton, 1956), p. 19.

[2] Nancy Goldstone, The Rival Queens: Catherine de’ Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois and the Betrayal that Ignited a Kingdom (New York: Hachette, 2015).

[3] Rob Davidson, ‘”Not Now, Not Ever!” (Gillard Misogyny Speech)’, 16 March 2014. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpavaM62Fgo.